The

Language of Live Interpretation -

Making Contact

By

John A. Veverka

Abstract

To be effective in interpretive communication, the interpretor must know as much about

visitor psychology and recreational learning principles as they do about the subject

matter they are interpreting. Making contact with the visitor requires that the visitor

actually understands the message or story that has been "interpreted" to them.

This paper provides some ideas and key questions for interpreting to museum visitors, and

considering their learning needs in developing the live interpretive program. A partial

interpretive planning strategy is provided on developing interpretive themes, measurable

interpretive objectives, and visitor analysis.___________

Interpreters must speak many languages! Not particularly foreign

languages, but rather the language of the everyday person. Depending on the site or

resource they are working with they may be called upon to speak:

- the language of children,

- the language of rural visitors

- the language of urban visitors

- the language of "experts"

- the language of local residents

- the language of tourists, and more.

In interpretive terms, this means that they must relate to the everyday lives of everyday

people. To help the interpretor do this there are a few general concepts and

principles of "recreational learning" that may come in handy. This paper will

look at not only how to speak the conceptual "language" of the visitor, but how

to make actual "contact" with your message or story.

Understand your visitors!

To be successful with live interpretation the interpretor should know as much about how

visitors learn and remember information presented to them as they do about the resources

or artifacts they are interpreting. It has been my experience that most museum

interpretors are well trained in the materials of the museum or historic site, but receive

little or no training in "visitor communication strategies". Here are a few

general learning concepts and principles that may be of use in preparing and delivering

your live interpretive program.

Learning Concepts:

1. We all bring our pasts to the present. Try to find out what the knowledge or

experience level of the visitors are related to your story or resource. Have they

recently been to other museums or historic sites? If so, which ones? Did they have a good

experience at those past visits?

2. First impressions are especially important. Make sure that the first impression the

visitors have of you and your program are outstanding! This may be your greeting with the

visitor at the start of the program, your appearance (are you in costume or uniform?) the

visual look of the program starting point or other non-verbal cues.

3. Meanings are in people, not words. If I were to say the work "tree", what

tree would come to your mind? We all have our own "visual dictionary" and

personal

interpretation of words. When you describe an artifact or other resource in a lecture what

does the visitors visualize? Make sure that you have the appropriate visual aides with you

to avoid "meaning" differences between you and the visitor. Be aware too that

most technical terms are new for visitors. Be sure to define them, don't take it for

granted that the visitors know what they mean.

4. Simplicity and organization clarify messages. The chief aim of interpretation is

provocation NOT instruction. During an interpretive program your job is not to make

the visitor a expert in history, science, art, etc. Your job is to inspire them to want to

learn more. Keep the program simple, focused, and fun.

Learning Principles:

Here are a few general learning principles that will help with the live

interpretationprogram planning and presentation.

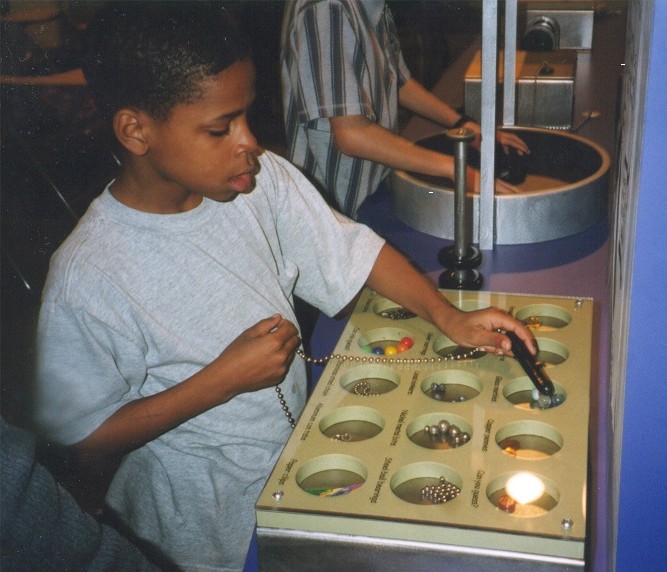

1. People learn better when they're actively involved in the learning process.

2. People learn better when they're using as many senses as appropriate.

3. People prefer to learn that which is of most value to them at the present.

4. That which people discover for themselves generates a special and vital excitement and

satisfaction.

5. Learning requires activity on the part of the learner.

6. People learn best from hands -on experience.

With these concepts and principles in mind, you should also remember the following.

Visitors remember:

10% of what they hear,

30% of what they read,

50% of what they see,

90% of what they do.

Planning for Content

To help insure success with the live interpretive program, it is helpful if the program is

actually planned. Every interpretive program should be planned for success. This would

include the following planning steps.

1. WHAT? What is the main theme of the program. A theme is expressed in a complete

sentence, such as "The logging history of Northern Minnesota still affects each of us

here today". Another theme might be "The early settlers of the Rouge River

Valley found creative ways to farm the valley". The interpretive program then

"illustrates the theme to the visitor".

2. WHY? Why are you giving the program? What are your objectives for the live

interpretation? The following are the three kinds of objectives that are needed

for any interpretive program to be "planned", with an example of each.

- Learning Objectives. At the completion of the program 60% of the visitors will be able

to describe three innovative farming tools invented by Rouge River Valley farmers.

- Behavioral Objectives. At the completion of the program the majority of the visitors

will want to look at the tools in the museum collection.

- Emotional Objectives. By the completion of the program the curiosity and interest level

in the visitors will be raised so that they will be motivated to want to look at the

museum collections, and attend other live interpretive programs sometime in the future.

Remember, objectives are measurable. They are also tools to help you focus on just what

you want your program to accomplish. As you consider the theme or topic for your live

presentation, and have written the

objectives you want the program to accomplish, there are two very important questions you

must ask yourself about your program.

1. Why would a visitor want to know that? This is an important question for you to answer

about the information you are planning to present. If you can't think of several reasons

why a visitor would want

to learn the information in your program, you have a problem! This is where you RELATE to

the visitor - give them a reason to attend the program.

2. How do you want the visitor to use the information you are interpreting to them?

If you don't want them to use the information, then why are you doing the program? The

answer to this question will become

your behavioral objectives for your program.

You don't want to spend a lot of time giving answers to questions that no one is asking!

3. WHO? Who are the visitors coming to the program? What is their age level,

knowledge level, interest level, etc. How much time do they have? What do you think

some of "their objectives" for attending your program might be? Any special

needs of the visitors (visual or hearing problems, handicap visitors, etc.).

Considering the What?, Why?, and Who? parts of your live interpretation planning will help

you focus you time and efforts. The answers to the "two questions" will

help make sure the program is relevant to the visitor, not just the curators or

resourceexperts.

The Three B's.

Interpretor's are in the BENEFIT business. Your interpretive program should be planned to

illustrate to the visitors (and agency managers) three benefits. You should consider how

the program will help:

- Benefit the site or resource. For example, will the

program help reduce damage to historic structures, or help keep visitors on designated

trails.

- Benefit the visitor. How will attending your program benefit the visitor? What's in it

for them? The answer to this question is what you use to advertise the program.

- How will your program benefit the agency you work for? More memberships? More gift shop

sales? Better political "image"?

What is the Product of your Product?

In doing live interpretation it is easy to get caught up in the "interpretation"

and forget what our real product is. By selling "the product of the product" you

put the idea of your program in a context that the potential user knows and understands

(relates to). For example, in the commercial world:

- Are you selling drills, or holes?

- Are you selling cosmetics, or "hope"?

- Are you selling new cars, or status?

What is the product of the product for your live interpretation?

- Are you selling looking at artifacts or valuing the cultures/people that made

them?

- Are you selling looking at rooms of furniture or pride in the people that made and used

the furniture.

- Are you selling "collections", or the benefits to all people in the saving and

conservation of historic materials?

To make contact...

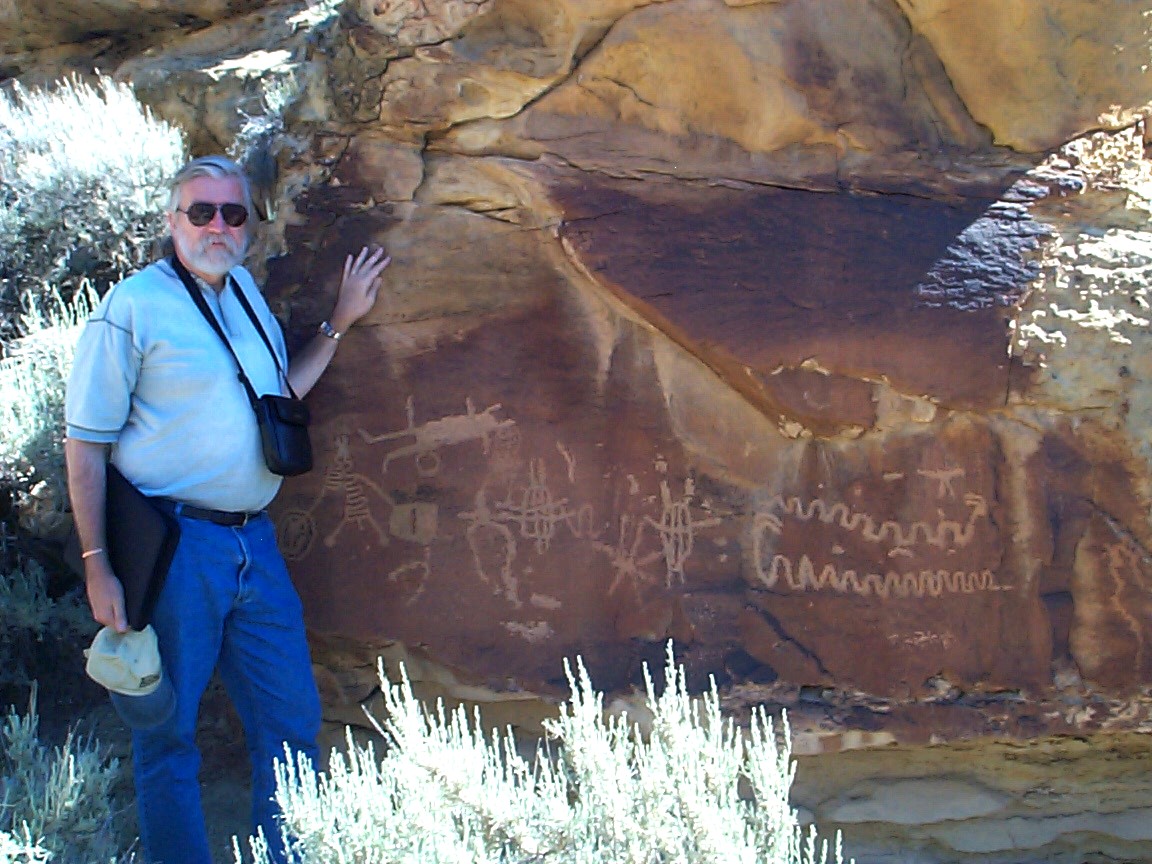

We know from years of interpretive research that the "live interpretor" is the

most powerful of all of our interpretive media and opportunities. The interpretor can

instantly "read" an audience, make adjustments in the program to help relate to

the different audiences they may encounter. They can look into the eyes of a visitor and

grab the visitors imagination and emotions. They can take a boring topic and make it come

to life for the visitors. But to be successful, live interpretation requires that the

interpretor think about and plan for their success. Being successful with any live

interpretive programs requires the interpretor to identify what they mean by success. The

successful interpretor will need to understand how their visitors learn and remember

information and how to provoke, relate and reveal the story to them. They will have a

focused message (theme) and objectives that they are going to strive to accomplish.

They never stop trying to improve their program and trying new ways of inspiring the

visitors. The reward the interpretor receives from his or her work really cannot be put

into words - a deep sense of satisfaction, pride, and more. The reward the visitor

receives from the interpretors efforts are equally as powerful. For when a trained,

focused, and inspirational interpretor meets with visitors hungry for inspiration,

something special

happens. They make contact and the journey begins.

References

Ham, Sam H. (1992) Environmental Interpretation - A practical Guide for People with Big

Ideas and Small Budgets. North American Press, Golden, CO.

Tilden, Freeman (1957). Interpreting Our Heritage. The University of North Carolina Press,

Chapel Hill.

Veverka, John A. (1995) Interpretive Master Planning. Falcon Press, Helena, MT.

John Veverka

jvainterp@aol.com